Chapter 6 Flight energetics and plasticity of the migratory flight

6.1 Mechanics and energetics of flight

During flight, a bird experiences two important mechanical forces, the weight, and frictional drag of the body (parasite drag) and the wings (profile drag). Normally, drag is around 1/10 of the weight. The more streamlined the body is the smaller the drag. Fast flying bird species are more streamlined (e.g. swifts) than slow flying species (e.g. pigeons). The wing is shaped as an aerofoil that produces lift when it is overflown by air. Birds produce both thrust and lift by flapping their wing. Among all forms of locomotion, flight is the one that requires most energy per unit of time. However, per unit of distance it is often quite efficient. Flight at low speeds is power demanding because wings have to be flapped at high speed in order to provide the lift to counteract gravity. At higher speeds, lift produced by the aerofoil shape of the wing increases without having to flap the wings. However, at even higher speed the profile and parasite drag increase so that higher speed need more power. The power vs. speed relationship, therefore, typically is U-shaped. Its minimum is at the speed at which the bird can fly with minimal power (minimum power speed). The greatest efficiency per unit of distance travelled is obtained at the maximum range speed, which is higher than the minimum power speed. These mechanics have implications for a migratory bird. Given a specific energy load (fat reserves), it can fly for the longest time if it flies at minimum power speed, but it covers longer distances if it flies at maximum range speed. Migratory birds may further minimize the time needed for migration, e.g. because it pays off having more time for other activities such as breeding or moulting, and therefore fly at even higher speeds.

## Warning: Paket 'afpt' wurde unter R Version 4.2.3 erstellt

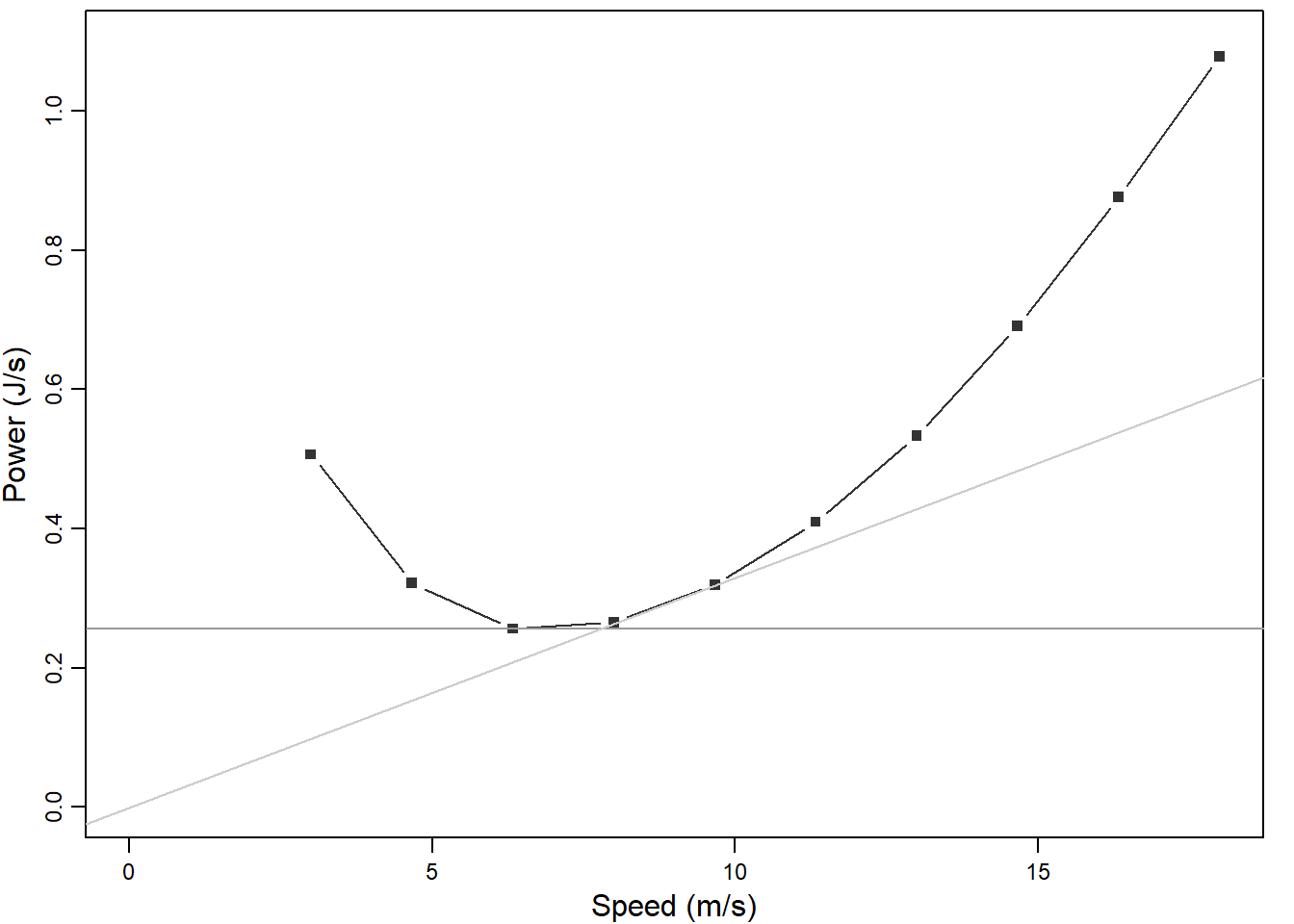

Figure 6.1: Mechanical power of flight in relation to flight speed for a hypothetical Robin Erithacus rubecula. Minimum power speed is the speed at which the power curve reaches its minimum (speed at which horizontal line touches the power curve). At the maximum range speed the distance per energy used is maximal (speed at which the tangent from the origin touches the power curve). The power curve is calculated using the R-package afpt

The relationship between mechanical flight power and speed depends on the morphology of the bird (Figure 6.1). Important factors are body mass, wing span and wing area. All else equal minimum power and maximal range speed increase with increasing body mass. Also body and wing shape play important roles. Seminal work on energetics of flight in birds has been done by Colins Pennycuick. He presents his life-long work in his book (Pennycuick 2008). Rayner (1990) gives a short introduction to flight mechanics wing morphology and migration performance. Anders Hedenström and his group investigate energetics of flight in migratory vertebrates, also including flapping flight (A. Hedenström and Alerstam 1998; Anders Hedenström 2009; Klein Heerenbrink, Johansson, and Hedenström 2015). They provide an R-package that allows exploring relationships between morphology and flight energetics (afpt).

6.2 Fuel for migratory flights

Among the three types of fuel (glycogen, lipids, protein), lipids contain the highest amount of energy per storage weight and therefore, lipids constitute efficient fuel for migratory birds. However, extramuscular lipids need a 1-2 hour mobilization period before the energy delivery is fully operating and even then, the rate of delivery is limited by physiological constraints (perfusion limitation, insolubility in plasma). Therefore, in mammals the relative proportion of energy from lipids during endurance exercise is always low. In contrast, birds can increase the proportion of energy derived from lipids to over 90% during endurance flights. In addition to lipids, the contribution of proteins is around 5% (L. Jenni and Jenni-Eiermann 1998). The additional use of protein may be advantageous for the water metabolism. Further, when body weight decreases due to depletion of fat reserves, it may be energetically advantageous that the flight muscles shrink in parallel.

6.3 Influences on migration

6.3.1 Endogeneous and exogeneous factors

How long birds stop-over is influenced by their body condition, food availability, time constraints and weather situation. Biebach (1985) caught Spotted flycatchers Muscicapa striata during their stop-over in an oasis of the Sahara desert. He deprived them from food and then allowed them restricted access to food and finally gave them food ad libitum. During the time with food deprivation, birds increased their migratory activity while body mass decreased. Migratory activity stopped when they received restricted access to food. During that period they increased body mass. Migratory activity started after they regained body mass. This experiment shows that birds decide between stopping-over and continuing migration based on their body condition and the food availability at the stop-over site.

Tracking of Marsh harriers Circus aeruginosis for several subsequent migration seasons has shown that individuals are highly consistent in the timing of migration whereas they chose different migration routes every year (Vardanis et al. 2011). This suggests that the timing of migration is more strongly determined by genetics whereas the route may be chosen opportunistically depending on wind situation or food availability, at least in the Marsh harrier.

6.3.2 Topography

Ecological barriers such as mountains, seas and deserts shape migration pattern. Most migrants choos routes side tracking ecological barriers. However, astoninglishly such barriers are regularly crossed by migrants. Individuals that cross the Alps, often are heavier and origin from more northern populations than individuals that fly around the Alps (Bruderer and Jenni 1988). Among the larger bird species regularly crossing the Alps, the ones normally using active flapping flight (e.g. falcons) predominate over those normally gliding by using thermal uplifts (e.g. storks). Migration density is lower above the Mediterranean compared to the Iberian Peninsula (Bruderer and Liechti 1998). Surprisingly, most birds crossing the Sahara desert only fly at night and rest over the day seeking a shadow place wherever they land (Schmaljohann, Liechti, and Bruderer 2007).

6.3.3 Wind

Wind has a strong impact on migrating birds. The costs for migration may be doubled or halved depending on wind condition. Some migrants rely on wind drift for completing their migration. Migrants start when wind conditions are favorable. During flight they choose the height at which they experience tail wind (Felix Liechti 2006). How strongly birds compensate for wind drift depends on age and differs between species. Generally, weak wind drift is compensated, whereas strong wind drift is only partially compensated.

6.3.4 Temperature

Temperature is important in two ways: First, temperature affects the migrating bird in flight. Second, temperature (together with other weather variables) acts via spatio-temporal distribution of food availability on the timing of migration. During flight, the bird has to cope with the body heat that is produced by the exercising muscles. This becomes more difficult at higher temperature. In wind tunnels, birds do not fly if temperatures are above 25°C. However, this contrasts with the observation of many birds flying at temperature above 25°C when crossing the Sahara desert during migration (Schmaljohann, Bruderer, and Liechti 2008). We still do not understand how birds cope with water loss and high temperature during migratory flights.

Temperature affects vegetation and the onset of spring. Effects of global warming on the timing of migration have primarily been studied during spring migration. Based on capturing data at three different ringing stations in Northern America, Marra et al. (2005) showed that long-distance migrants migrate earlier in warm springs compared to cold springs, thereby 1°C warmer corresponded to 1 day earlier migration. However, the vegetation budburst advanced by 3 days, thus showed the three-fold reaction. They further showed that the speed of migration was faster in warm years compared to cold years. It seems as if long-distance migrants may be able to adjust their timing of spring migration to some limited extent to an earlier vegetation burst. Similarly, Both (2010) could show that Pied flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca adjusted the timing of spring migration rapidly to changing climate when conditions on migration are favorable. However, such adaptation of the timing happens not in all populations to a similar extent. Several studies found that conditions on the migratory route are important for the timing of migration (Hüppop and Winkel 2006).

In general, short-distance migrants adapted their timing of migration to a higher degree than long-distance migrants. In the latter, timing seems to have a stronger genetic bases. Further, their migration is affected by changing conditions across a wide geographic range.

Further reading: Felix Liechti and McGuire (2017) compare migration flyways, timing of migratory flights and staging and flight behaviour between birds and bats.